The Great Deception: The EU Was A Scam From The Beginning

By Morris van de Camp

Christopher Booker & Richard North

The Great Deception: The True Story of Britain and the European Union

Revised Fourth Edition

London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2021

In 1992, the Maastricht Treaty transformed the European Economic Community into the European Union (EU). This transformation created a “government of Europe,” with its own foreign and defense policies. This treaty also thrust Britain directly into the affairs of Europe. Every European social fad, repressive regulation, and military provocation became a British problem until the British left the EU in 2020. Even before Maastricht, however, the British were paying heavily for their involvement in Europe.

Historically, the British have worked to keep themselves clear of the quandaries of Continental Europe. The British opted for trade with the outside world, the freedom of the open ocean, rather than the chains of a European alliance. How then did Britain become so completely ensnared by Continental Europe just after the fall of the Soviet Union? It turns out, this was done by deceptive means year after year on the part of nearly all of Britain’s political elite after 1955. Other than Margaret Thatcher, every British Prime Minister who followed Winston Churchill’s second term supported increased British involvement in what would become the European Union, and for what Prime Minister Edward Heath called “presentational reasons,” deliberately concealed the full truth of what was happening to the British public.

Richard North and the late Christopher Booker are remarkable authors and intellectuals who first described this situation in their 2003 book, The Great Deception, which has been continuously updated and re-published. (The version in this review was printed in 2021.) This book helped pave the way for Great Britain’s exit from the European Union—or Brexit. Their book, and its incredible impact, stands as a testament to the power of the pen and the importance of metapolitics in shaping public policy. The book’s focus is on the facts of the events as they happened, and that gives the ideas presented therein enormous power.

Europe—1916 to 1945

The core principles of the EU originated, ironically, at a time when Europe was bitterly divided, in 1916, during the Battle of Verdun. The tremendous spasm of violence at Verdun was as much a test of industry as it was of fighting prowess. The Germans supplied their abundant, well-designed artillery systems with ammunition still warm from the manufacturing process. The French had fewer and less-capable guns and less ability to produce shells at the rate needed.

As the artillery problems mounted, the French government turned to industrialist Louis Loucheur to come up with a solution to the problem. Loucheur was an early pioneer in the use of reinforced concrete and one of the few French technocrats familiar with mass-production techniques. Loucheur turned things around for France, and he came to realize that European warfare relied on industrial organization which in turn relied on energy (coal) and building materials (steel). He concluded that should the control of steel and coal be put into the hands of a “higher power” rather than the individual French and German governments, peace might be preserved.

The idea that supranational control of coal and steel could create peace was reinforced by the events surrounding France’s temporary occupation of the Saar—a coal-rich part of Germany—after World War I. The French occupation of the Saar basin was part of the wider, security-focused allied occupation of German territory in the 1920s as well as a French attempt to gain financial reparations from war damages. This occupation and its associated economic rip-off destabilized Germany and the disorder spread to the rest of Europe. In addition to the fact that the French government was appropriating German coal and disrupting the German economy, the French Army used colonial sub-Saharan African troops, who ran amok and abused the population.

The poorly behaved French colonial soldiers triggered a widespread campaign of non-cooperation on the part of the Germans which then triggered French reprisals that included summary executions of German civilians. The disorder caused a collapse of Germany’s industrial output, and unemployment followed. The German government responded by guaranteeing the wages of the unemployed workers and printed the money to pay the unemployed. The money-printing created mass inflation. The crisis was temporarily solved in the mid-1920s, when Germany was admitted to the League of Nations and the German Chancellor Gustav Stresemann and the French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand, agreed to create a “United States of Europe.” Then the Great Depression started, and Germany fell to the National Socialists.

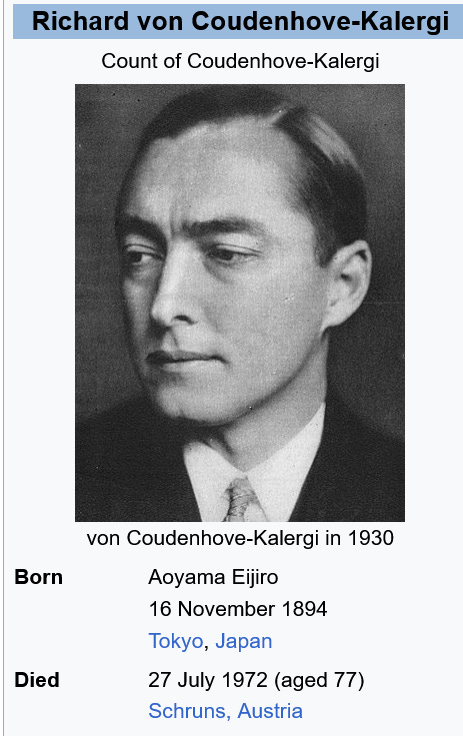

Another important organizer of the united Europe project was Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894-1972). His father abandoned a diplomatic career to be a world traveler and died young. Coudenhove was also half-Japanese. As he lived his life, his citizenship bounced from Austro-Hungary, to Czechoslovakia, then finally to France. In 1922, while still a very young man himself, Coudenhove published the book Pan Europa. The book inspired a generation of European diplomats who strove to create a unified Europe.

When World War II came, the National Socialists also attempted to create a unified Europe, but this was really a policy of subordinating the economy of the Continent to that of Germany’s. The Nazi policies had some overall overlap with those of the modern European Union, but the men who developed what became the European Union were all bitterly opposed to Nationalist Socialist Germany and Fascist Italy. One such Europeanist was the Italian Altiero Spinelli (1907-1986), who was a communist who opposed Mussolini and was imprisoned for a dozen years. Spinelli broke with communism while jailed and wrote, along with fellow prisoner Ernesto Rossi, the Ventotene Manifesto in 1941. In the manifesto, Spinelli and Rossi proposed a federalized Europe.

The Uniters Among the Post War Ruins of Europe

After World War II, the anti-fascist Europe-unifying men, such as Spenelli, moved into policy making positions. The key figure at this time was the Frenchman Jean Monnet (1888-1979). Monnet’s first experience in united European operations was during World War I, when he was on the Inter-Allied Maritime Transport Council, which coordinated war-related shipping.

During the Second World War, Monnet worked for the Franco-British Economic Co-ordination Committee and after 1943, served in Algeria with the Free French government. After metropolitan France was conquered by the Allied forces in 1944, Monnet moved there and devised economic policies to rebuild France.

In 1950, Monnet proposed unifying the market for Western Europe’s coal and steel industries 34 years after the idea was first expressed by Louis Loucheur during the Battle of Verdun. Eventually six nations, West Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg, signed on. Monnet served as the president of the European Coal and Steel Community until 1955. At this time, it was domestically impossible for the British to join this organization. Prime Minister Clement Attlee political base consisted of the kind of men who worked in the coal pits in the north of England. Attlee recognized “the Durham miners” wouldn’t support such a scheme.

Meanwhile the implications of this economic unification were hidden under the spectacular events of the time. In the late 1940s, the British Empire, which had been at its height immediately following World War I, started to collapse. Additionally, there were the lingering economic problems across all of Europe due to the destruction wrought by the war. While Britain was somewhat hungry in the late 1940s, the rest of Western Europe starved. Then the Cold War began. In response to the problems, the Americans adopted the Marshall Plan which rebuilt the region and provided food. The Marshall Plan forced Western Europe’s nations to cooperate since the Americans provided the aid regionally, to put it simply.

The troubles at home and abroad both helped and hurt both the formation of what became the European Union and Britain’s entry into it. The decolonization struggles faced by France caused continuous domestic political shifts in Paris, so Europe-focused government officials such as Jean Monnet became the few senior officials who were continuously in office, so their influence grew.

In the 1950s, President Eisenhower, partially acting upon his Quaker-like upbringing in the American Midwest, proposed sharing nuclear technology with the various nations of Western Europe, with, of course, conditions. This caused the French, through Monnet, to create the Euratom Program, which allowed Western Europeans to cooperate in the development and use of atomic technology without American conditions. The West Germans supported Euratom to get access to atomic weapons so that they could counter the Soviets should the American military withdraw from Europe. As it happened, the French acquired the atomic bomb in 1960, and the US Army provided atomic capable artillery batteries as direct support to the West German Army until the Cold War ended. Either way, atomic politics caused the Western Europeans on the Continent to better join together. Britain, which already had atomic weapons was not part of this process, however.

In 1956, the British were humiliated during the Suez Canal Crisis, while a few months later, the Continental Europeans triumphed diplomatically with the 1957 Treaty of Rome which transformed the European Coal and Steel Community into the European Economic Community. Chastened by the disaster at Suez and looking for new successes, the new British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, applied to join the EEC, but his application was blocked by France’s President Charles de Gaulle in 1963 who channeled the anti-English attitudes of Napoleon with his veto message saying,

England, in effect is insular. She is maritime. She is linked through her trade, her markets, her supply lines to the most distant countries. She pursues essentially industrial and commercial activities and only slightly agricultural ones. She has, in all her doings, very marked and very original habits and traditions. In short England’s nature, England’s structure, England’s very situation differs profoundly from those of the Continentals. (p. 101)

Many British patriots point to this statement as proof of Britain’s preexisting cultural inability to join and thrive within a Continental European political and economic system [Charles de Gaulle knew it: Britain does not belong in the EU, by Charles Moore, Spectator, May 1, 2016] However, it is possible that de Gaulle’s veto was based on more complex problems. France was going through a farm crisis at the time, and there was French frustration stemming from the fact that the British got top shelf rocket and missile technology from the Americans which could carry British-made hydrogen bombs. American military aid to France wasn’t nearly as generous. In 1967, de Gaulle vetoed British entry a second time.

Charles de Gaulle left office in 1969 and was followed by Georges Pompidou. When Edward Heath became Britain’s Prime Minister in 1970, the two worked to ease Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community. From 20-21 May 1971, Heath and Pompidou met, and the meeting went so well that French support for Britain’s entry into the “common market” was assured afterwards. During the meeting, Britain agreed to support the European Economic Community’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) which remains Europe’s most expensive and politically explosive economic protocol. While Heath could revel in the fact that he’d finally won over the French,

The cost to Britain had been enormous. She had been saddled with an enormously expensive CAP, already costing as much each year as the Americans were spending on reaching the moon, with its in-built bias in favor of France. She had agreed to comply with 13,000 pages of legislation that she had no part in framing, and was now committed to enact all future legislation passed by the Community, whether or not in her interest. She had agreed to subordinate her courts to a higher court against which there was no appeal. In anticipation of economic and monetary union, Heath had undertaken to undermine sterling’s position as a reserve currency. And, while securing minimal concessions for a few Commonwealth countries, he had committed Britain to make a hugely disproportionate contribution to the budget. (p. 123)

Britain officially joined the European Economic Community on 1 January 1973 after pro-Europe parliamentarians in all parties joined to beat back the anti-Europe faction in the Labour Party. The specifics of who talked to who and what backroom deals were cut to get Britain in the EEC was kept secret, but the secrecy hardly mattered, Parliament ratified Britain’s entry.

Europe Steals Britain’s Fish

Britain’s fishing industry became the next economic casualty of Britain’s European Economic Community ensnarement. When Britain joined the EEC, Europeans gained access to Britain’s traditional fishing grounds right up to the beaches of England. As a result, British fishing grounds were soon raided by Continental Europeans.

Britain’s fishing industry also paid heavily for British involvement in NATO, itself an organization only made necessary by the aftereffects of the unsolicited British war guarantee to Poland in 1939 which led to World War II and the following Cold War. Another problem appeared in the North Atlantic when the Icelandic government declared an exclusive fishing zone which would ultimately extend 200 miles from Iceland’s coastline. This cut British fishermen off from waters they’d fished in for centuries.

To enforce their expansion, the Icelanders confronted British fishermen with armed warships and cut the nets of the British fishing boats. Eventually, British fishermen were accompanied by vessels from the Royal Navy and an Icelandic Coast Guard ship was rammed by a British frigate. These actions led to a diplomatic uproar. The British were forced to back down when Iceland threatened to withdraw from NATO. Iceland’s threat was not empty, without that island, it was impossible to cover the Greenland-Iceland-UK Gap through which Soviet air and naval forces could pass. The underemployed men in places like Clacton-on-Sea are the direct result of effectively paying freeloading “allies” enormous economic concessions for their compliance. Likewise, the underemployed men in America’s Rust Belt also pay for the compliance of “allies” like the South Koreans.

Other problems surrounding fishing occurred because of Britain’s ensnarement by the EEC and the following EU. Spanish fishermen registered their boats in Britain and purchased British fishing licenses, but they’d offload their catches in Spain. The Danish were also able to carve out a large portion of the North Atlantic for the exclusive use of their industrial scale fishing boats. European regulations had no quotas for by-catches so many species of fish were dumped, dead, back into the ocean, which was both a waste and ecological disaster.

More Structural Problems Appear

Throughout the 1970s, Britain was an economic basket-case. The unions controlled the country and strikes were frequent. The British workingmen had also picked up a professional culture of absenteeism and go-slow behavior when not on strike. British industry was obsolete even before the Second World War and completely outclassed by Germany in the 1970s, so most of the remaining British factories closed. Meanwhile, the British taxpayers continued to subsidize the EEC bureaucracy and its members’ economies.

It was during Harold Wilson’s time as Prime Minister that the full extent of the problems between Britain and Continental Europe appeared. One such problem was that British businessmen lost the protection of British law due to the Treaty of Rome,

On 22 November 1974…[Judge] Lord Denning…ruled in favor of a German company that had demanded an English customer should settle his disputed bill in deutschmarks. In a lower court the company had already been given judgement in sterling, this being previously the only currency in which an English court could legally make an award. But the German firm had appealed because, by then, sterling had been substantially devalued against the mark. (p. 160)

By the mid-1970s, the British political elite was also starting to feel the burden of integration with Europe. Parliamentarians had to add time to debate the EEC’s issues which cut away discussions on other matters. Despite these problems, Britain’s involvement in the EEC was bolstered in 1975, when the British government held a non-binding referendum as to whether Britain should stay in Europe or not. The British public voted to remain in the union, with England being the center of pro-European attitudes while Scotland’s Western Isles and the Shetlands voted against involvement in the EEC.

The results of the referendum are curious because the escalating costs of involvement in Europe were blindingly obvious to any careful observer by 1975. However, this truth was hidden from the public by an effective pro-Europe propaganda smokescreen. In the weeks leading up to the referendum, the pro-Europeans in the British Establishment downplayed or hid the problems with involvement in Europe and flooded the media with pro-Europe stories and advertisements. The campaign leading up to the referendum is unique in that British Civil Servants were encouraged to campaign for Europe. Previously, British Civil Servants were apolitical.

Conditions continued to deteriorate despite the public’s optimistic attitudes,

…[T]he relationship [between Britain and the European Economic Community/European Union] was more or less doomed from the moment Wilson arrived in Brussels on 16 July 1975 to attend the first European Council after the referendum—only the second formal Council to be held. The prime minister had announced that he would stand up for British interests ‘no more and no less than our EEC partners’, an apparently innocuous statement intended for domestic consumption. Nevertheless, it was seen in Brussels as ‘alarmingly negative’. (p. 165)

French politicians also made negative statements towards the EEC for domestic consumption but,

…[W]hile such statements were acceptable from the Fifth Republic, when British politicians indulged in anything like the same rhetoric, Britain, and Britain alone, became the awkward one. (p.166)

After the Bretton Woods financial system collapsed, Europe’s central bankers attempted to create a common Exchange Rate Agreement, but this too became a problem. “Only West Germany, Benelux and Denmark managed to keep within the margins [of the exchange rate agreement], creating in effect an expanded Deutschmark zone.” (p 172) Britain’s financial industry, therefore fit poorly into the wider European structure and this harmed the British economy year after year.

The Thatcher ‘80s

Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister in 1979 when Britain was facing a crisis in Northern Ireland and the Cold War. Domestically, the British economy was shackled by powerful unions and industries which had been nationalized. These industries were unprofitable and cost the treasury dearly.

Thatcher confronted all the problems head on. Her courage was infectious. Most importantly, she’d learned how to make high ego people conform to her demands, which at the time, were bold and unorthodox—such as closing unprofitable state owned-coal mines. She also headed a political party which supported British involvement in the European Economic Community. It was her rival party—Labour—which had a core of anti-Europeans within.

However, Thatcher took a look at what was going on in Europe and she started to frankly remark on the problems of the EEC pointing out that,

We haven’t yet got a common market and we’re a very long way from it. I must tell you that I do not believe in what I would call a United States of Europe. I do not believe in a federal Europe and I think to ever compare it to the United States of America is absolutely ridiculous. (p. 197)

Thatcher also supported a federalized European government rather than one that was a centralized bureaucracy. In 1988 she said,

Willing and active co-operation between independent sovereign states is the best way to build a successful European Community … Europe will be stronger precisely because it has France as France, Spain as Spain, Britain as Britain, each with its own customs, traditions and identity. It would be folly to fit them into some sort of identikit European personality. (p. 222)

Margaret Thatcher’s political rise was made possible by the fact that she correctly interpreted the data throughout her career. She recognized the data pointed out that the European Economic Community incurred greater costs to Britain than benefits. Although Britain was the second-largest overseas trader in the EEC, for example, the Community negotiated as a block with the Global Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. The Community also ensured France’s interests were protected and Britain’s ignored. Thatcher also recognized that the EEC’s governing bureaucracy was seeking to create a supranational, centralized European government.

On 31 October 1990, she went to Rome for a summit meeting where the idea that Britain scrap sterling for an eventual European currency arose. She responded, famously, “No, no, no!” The remarks came at a time when Thatcher was becoming more “authoritarian” with her cabinet and those ministers were looking for an excuse to revolt. Thatcher had also suffered a political blow earlier that year when a change in the tax code led to nationwide rioting.

Meanwhile, Thatcher had dedicated pro-Europeans in the Conservative Party and on her cabinet. One such person was Geoffrey Howe. He was a mild-mannered senior official who responded to Thatcher’s “No, no, no!” remarks the way the wife of a clergyman would if that minister suddenly proclaimed his disbelief in God. The day after Thatcher’s remarks in Rome, he resigned. His speech unraveled Thatcher’s control over the Conservative Party and she was replaced by John Major.

Britain & Europe During the End of History

Thatcher left her successor a war in the Persian Gulf, which required a force of 50,000 British servicemen, and an economic recession which couldn’t be shortened by lowering interest rates. Because of Britain’s involvement with the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, the Exchequer was required to keep interest rates high—reaching 15% at one point.

On 25 June 1991, a few months before the Soviet Union collapsed, Slovenia and Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia. The Europeanists saw the opportunity for “Europe” to save the situation. They arranged for the Council for the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) to meet in Berlin, where they declared that they supported the territorial integrity of Yugoslavia. This was an enormous mistake,

The Council was simply unable to grasp why the peoples of Slovenia and Croatia would do anything to break away from the tyranny of Belgrade, which had held them in its grip since 1945. Since the whole purpose of this Council was to discuss building a new federal government for ‘Europe’, the [Council] could hardly be expected to welcome the idea of another federation collapsing. (p. 244)

The root cause of the Yugoslav Wars was the incredible power of national identity on politics. The members of the CSCE should have known better, the fierce ethnic politics of Yugoslavia was manifest even when that polity appeared outwardly peaceful. Croatian ethnonationalist terrorists had blown up an airplane in 1972 and hijacked another in 1976.

The inability for the top European diplomats to understand the internal dynamics of Yugoslavia indicated a serious flaw in the entire system. The flaw can be traced back to the author of Pan Europa, Count Coudenhove-Kalergi, whose father rejected genuine responsibilities for a short life focused on tourism while taking on an ill-advised marriage to a foreign woman. This failure for a high-born person to seek and gain responsibly is a marker of fecklessness, and the inability understand national differences doesn’t indicate an open mind, it demonstrates an empty and inert one.

While the Yugoslav Wars burned, the European Economic Community became the European Union and the Union picked up Austria, Finland, Sweden, and Norway in 1995. On the horizon was absorbing the formerly communist countries. Also on the horizon was the adoption of a single currency. The new additions and the common currency increased the supranational European bureaucracy’s power while poisoning Britain’s domestic politics. Nothing Prime Minister John Major did to respond to these developments worked in his favor. When Major pointed out that taking on new countries altered the balance of power within the EU and harmed British interests he was attacked from one quarter, when he attempted to compromise, he was attacked by another group.

The Start of the Unraveling

While the sun was setting, unnoticed at the time, on the happy days of the End of History, four major problems within the European Union predominated. The first was the question as to where power should reside—the supranational EU bureaucracy in Brussels or in the various national governments? Then there was the problem of enlargement, especially to the east, where everything and everyone is poorer. The third issue was the Common Agricultural Policy—which sought to unify farming policy in climate zones that stretched from the Arctic Circle to the dry plains of Andalusia—was becoming a major drain. In the 1990s, Poland had a farm crisis which matched France’s crisis of the 1960s. Finally, the EU bureaucrats recognized what they called the “democratic deficit.” The “citizens” of Europe were seeing the EU supranational government as unaccountable and remote.

While these problems occurred, the Europeanists were seeking to launch a unified currency—which came to be called the Euro (€). The British political elite was divided over adopting the Euro. Tony Blair hailed the new currency as a “turning point” for Europe, which caused The Sun—a British tabloid—to question whether Blair was “the most dangerous man in Britain” on 24 June 1998.

Sun readers “rounded” on Blair as a response to this headline. The attack was a shock to Blair, The Sun was a newspaper which normally supported him.

The Euro was launched on 1 January 1999 at the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. A band ironically played “Land of Hope and Glory,” a patriotic British song although the British public and political class was becoming increasingly skeptical of adopting the common currency.

Britain’s rejection of the Euro was the start of a larger unraveling. In early 2001, the problems with the Common Agricultural Policy and the “democratic deficit” came together. In northern England a hoof and mouth disease epidemic broke out. In an era of good government, the answer to such an event would be a large-scale vaccination of the animals. However, the British government was not prepared to attempt this, and the European Union was even less able. As a result, the British followed some slap-dash EU guidelines and conducted a mass slaughter and burial of the infected animals. The English farmers in the North of England were enraged by the sight of so much livestock buried in an abandoned airfield. It was here that the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), which was founded in 1993, after the Maastricht Treaty went into effect, started to make real gains.

Meanwhile, Britain and the European Union diverged over the response to 9-11 and the Iraq War. Indeed, France had been supplying weapons to Iraq despite the sanctions, thus increasing the mistrust and frustration all around. While EU ambitions supported a common military policy, the European militaries had little capability to deploy and support a field army. The Americans and British militaries did the heavy lifting in 1999’s Kosovo War.

The problems of Britain’s involvement in Europe popped up in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars also. The British Army went into Iraq with light, unarmored vehicles acquired for ease of deployment along the standards set by the European Rapid Reaction Force. As the casualties mounted, the British shed their European vehicles for armored American-made ones. Meanwhile, the EU’s Constitution failed to be ratified, a version of it was enacted with the Treaty of Lisbon, which Britain ratified in 2008.

Parliament’s ratification of Lisbon is an example of the fact that at the point when most human institutions appear to be infinitely stable, the sand under that institution has shifted, and the thing is on the way towards collapse. Britain’s involvement in Europe was problematic from the get-go but it took until 2001 for serious resistance to the EU to truly form and make gains. The anger over Europe started with the working class—fishermen, shepherds, and soldiers—angry at cut nets, mass livestock slaughters, and the shredded bodies of soldiers. It spread to upper class politicians who became vocal Euroskeptics and UKIP supporters.

Endgame

Neither UKIP nor any of the other Euroskeptic parties won any major victories—such as capturing the Prime Minister job. Instead, the Euroskeptics won small victories and otherwise caused defections from the main parties, especially the Conservatives. This caused the mainstream parties to adjust course. Meanwhile, the Euro nearly collapsed as a currency in 2009. The crisis was centered on Greece, which had a culture of tax dodging, an underemployed economy, and a workforce which tended to seek jobs in Germany. During the crisis, it was abundantly clear that Britain had dodged a bullet in keeping the Pound.

The issues surrounding the EU’s expansion were also not resolved. As the EU marched eastwards, Britain was inundated by Eastern European workmen who drove down wages and a large host of criminal gangs and desperate Eastern European migrants. At the same time the European Union’s members would continuously pursue their own respective national interests in a disingenuous way within the EU framework.

Then there was Islamic immigration. When William Penn argued for a united Europe in the seventeenth century, he pointed out that European unity would protect against the inroads of the Islamic World—then led by the Ottoman Turks. He wrote, “Another Advantage [of a United Europe is], The Great Security it will be to Christians against the inroads of the Turk…” In 2015, the Germans ignored EU migration rules and allowed many military aged Syrians to enter. This caused considerable disruptions across Europe and several Jihadist massacres.

A year later, the British voted to leave—Brexit. The results were opposite of that of 1975. The center of anti-European attitudes in 2016 were in England, with Scotland voting to remain. In 2020, after considerable political sausage-making and political shifts, the British negotiated the UK-EU Treaty. Britain was free of Europe, but now faces the crisis of its non-white immigrant population.